Did you know that H.G. Wells, the Victorian author famous for penning science-fiction classics such as The War of the Worlds and The Invisible Man, was also a miniature war gamer?

The first edition of cover of Little Wars.

Despite being avidly anti-war in real life, Wells is responsible for developing one of the first mass-market miniature war game rulebooks, published in 1913 under the title Little Wars. This little rulebook, clocking in at only 111 pages, was the first commercial miniature wargame rule set to include rules for simulating land-based warfare. Prior to Little Wars was Fred T. Jane's Rules For the Jane Naval War Game, first published in 1898, which is widely credited as the first mass-market miniature wargame rulesbook. The book contained rules for simulating maritime warfare, with players commanding fleets of miniature ships made out of cork (a far cry from the spectacular sculpts from the likes of Games Workshop that we see today).

Jane's cork battleship (Top) versus an Arkanaut Frigate from Age of Sigmar (Bottom). Who wore it better?

Prior to these publications, wargaming was largely the purview of actual militaries, who used war games as a training aid. One of the most famous examples of these granddaddies of tabletop wargaming is the "Kriegsspiel" (literally translating to "war game") that was used by the Prussian and German militaries to help its officer corps practice tactics and strategy.

These games were notably more complex than many of the modern war games that we are familiar with, with robust rules governing communications, movement, logistics, the "fog of war", and the individual combat capabilities of each unit. Their complexity often necessitated the presence of an umpire or "gamesmaster" who would make rulings regarding the moves of each commander. While useful as a training exercise for the highly disciplined Prussian army, these cumbersome rule sets likely held little appeal outside the military.

A very involved session of Kriegsspiel. Don't they look like they're having fun?...

Unlike the Kriegsspiel, Little Wars was designed with accessibility in mind, intended to be "played by boys of every age from twelve to one hundred and fifty - and even later if the limbs remain sufficiently supple - by girls of the better sort, and by a few rare and gifted women." (Never underestimate the power of Victorian casual sexism, I guess). Thus, it was designed from the ground up to be a product for play rather than training.

Wells' rule set was developed with the help of his friend Jerome K. Jerome, the impetus for the idea occuring to the two gentlemen "while shooting at toy soldiers with a little cannon after dinner one night." Their conversations and experimentation eventually led to the development of Little Wars.

Despite being a relatively simple set of rules by modern standards, and having very little random elements, Little Wars includes many specific gameplay mechanics and tropes that can still be found in our favourite war games today.

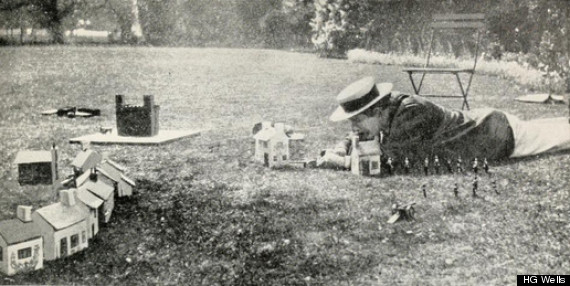

For example, the maximum movement for infantry units is listed as one foot, while the maximum movement for cavalry is two feet; movement standards that should be familiar to any modern war gamer. To provide a variety of gameplay, Little Wars contains multiple mission types that change the objectives of the game and the deployment of the players' miniatures (Fight to the Finish, Blow at the Rear, and the Defensive Game). The book also contains a morale system, with units becoming "isolated" allowing them to be taken prisoner. The rules set also used "true" line of sight rules, with players bending, crouching, or getting on their hands and knees to see what their soldiers "see".

Wells, getting a soldier's-eye view of the battle.

Despite these similarities to modern miniature war games, one notable difference is the use of toy cannons. Players could use these cannons to shoot projectiles at the opposing ranks of miniature soldiers, knocking them down and "killing" them. (Try asking any modern wargamer if you can shoot missiles at their finely painted miniatures - see how that goes).

Little Wars also includes a chapter detailing a specific battle conducted by Wells, titled the "Battle of Hook's Farm". This chapter, with it's labeled map diagram, turn-by-turn exposition (written in Wells' wonderful and witty prose), and photographs of the battlefield (taken by Wells' wife Amy Catherine Wells, acting as a "war-correspondent"), is nearly indistinguishable from the modern "battle reports" that war gamers record and share even today. Looking back 105 years, this remarkable little book reminds us that inspired game design can last for generations.

The first pages of the "Battle for Hook's Farm" (Top) and a battle report from the May 2018 issue of White Dwarf Magazine (Bottom).

If you are interested in reading Little Wars yourself, the book is currently in the public domain, and can be read on Archive.org or Project Gutenberg.

And if this feature has got you into the war gaming mood, it might be a good time to remind you that our store carries several lines of fun and exciting war games such as Warhammer: Age of Sigmar, Warhammer: 40,000, Star Wars: X-Wing, and the Star Wars: Legion.